Change is upon us in a way we’ve never known. Certainty, Order, your Future…all gone. As leaders, as human beings, we aren’t designed to embrace unpredictability. Don’t want it. Not good at it.

If COVID has revealed anything, it’s how complacent and tranquilized we have become in what Thomas Kuhn called “normal”. We’ve gotten lazy, fat, and justified. Creativity and innovation have been nice-to-haves, labelled as soft-skills. If you had budget, you might even have an ideation workshop with an “expert”. All of this is some version of playing doctor, a weak warm up act for the real game of change or die that most companies are now playing.

It’s becoming blatantly obvious that reinventing yourself and your business is the only thing that will have you survive and positioned to grow when we come out of it.

Yet, we are all extremely weak at navigating disruption and finding opportunity in the midst of chaos.

Why is that?

And what can we do about it?

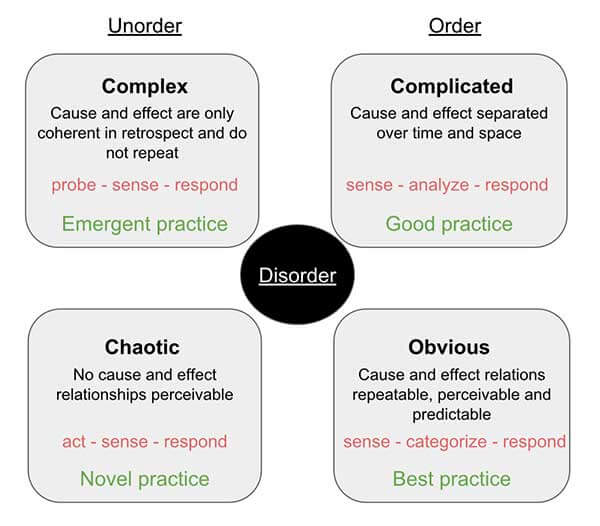

There are answers in exploring the potency of the Cynefin (sense-making) Framework.

The right side of the framework shows situations with order or predictability; the left shows situations with little to no order and predictability.

Ordered & Predictable

Predictable circumstances range from obvious to complicated.

In Obvious circumstances, cause and effect are clear, plain as day. We sense (see, hear, etc.) what is happening, categorize quickly, and respond by taking obvious and appropriate actions. The situation values rapid categorization. It is the domain of practice. Action follows a tried and true formula that has repeatedly produced results. e.g., we sent the wrong invoice amount and a client is upset, so after brief consideration:

- I hear what happened from my assistant [Sensing]

- Quickly decide this is too important to leave to the salesperson [Categorizing]

- Call the client directly to apologize [Respond]

- And re-issue the invoice with a credit for their next purchase [Respond]

For most business leaders we are dealing with the impact of COVID-19 on our businesses as if it was an obvious phenomenon. We think that we can use the heuristics and principles that were appropriate pre-COVID. If we somehow just apply what we’ve always known and always done, with a little “twist” or two, we can get through this. This is the devastating shortcut that every human being is born to take when faced with something new, and it is why most businesses fail in a crisis. This article is about distinguishing the trap you may be in, and exiting – pronto!

In a Complicated circumstance cause and effect are not obvious and taking the right actions requires real thinking and bringing expertise into the conversation. We sense (usually, see and hear) what is happening, take time to analyze and evaluate the situation, and then respond by taking the action which is not-at-first-obvious. The situation requires and values logical analysis, the ability to objectively compare and evaluate. There are usually multiple ways to get the desired outcomes. Experts may not agree on how to begin, but they are aligned on what direction to go. This is the domain of good practice rather than best practice. e.g., our long-term client was upset after our top salesperson, whom they love, met with them on Wednesday, so I will:

- Call my VP of sales and my performance coach to discuss. One says to call the client first, the other says talk to my salesperson first. They offer different starting points but are aligned on talking to both parties. [Sensing]

- I call the salesperson first and ask what happened until I am clear I understand her perspective. [Sensing]

- I call the client and ask what happened until I am clear that I understand his perspective. [Sensing]

- I bring back what I discovered to my coach and get her perspective [Analyze]

- I choose to speak to each of them again separately, share my discoveries and expand their view of what happened, finally creating a call for all three of us and make sure peace is restored [Respond]

- I close the loop with my VP and my coach so that they can assess the efficacy of their advice. [Respond]

Obvious or Complicated is where most of us have been operating pre-COVID; some state of business-as-usual. Our strategic plans, many looking much like last year’s, have had a luxurious 3 to 5-year window. This state empowers continuity and continuous improvement. The mindset is one of increasing efficiencies, cutting costs, and increasing profits. It is the state of incrementalism.

In this condition of “normal”, there is no perceived urgency to disrupt ourselves, much less disrupt the industry. We are effectively waiting to be disrupted by some upstart and then react by doing more of what we have always done. The rationalization is some version of “this is what has made us great”. Most leaders live and spend most of their time here; trying to ensure continuity and, in fact, protect the company against discontinuity or disruption. It’s logical. The problem is that the state of continuity is NOT the current state we’re in now.

In fact, consider that COVID has only revealed and sped up what has been there all along; the great threat multiplier. COVID has revealed that we were always vulnerable to a disruption in the market or a sudden shift in our industry. When Jack Welch, Chairman of the Board and CEO of GE, said “Change before you have to” in 1989, it quickly entered the circus of cool quotes that hardly any leader actually implements.

The long list of poster children for the wait-to-be-disrupted business model includes—Kodak, Enron, Blockbuster, GM, Schwinn, Sears, Marvel Entertainment, Readers Digest, Toy R Us, and thousands more. Many of us now stare down the self-imposed barrel of the same gun.

Unordered & Unpredictable

The current COVID-19 crisis lies on the left side of the Cynefin Framework. This world of unorder and unpredictability has circumstances ranging from complex to chaotic. It’s where many business leaders find themselves right now, unable to predict just about anything. Let’s look at each domain.

The current COVID-19 crisis lies on the left side of the Cynefin Framework. This world of unorder and unpredictability has circumstances ranging from complex to chaotic. It’s where many business leaders find themselves right now, unable to predict just about anything. Let’s look at each domain.

In Complex situations, cause and effect are only apparent in retrospect, e.g., Italy locks down the country on March 9th with 1797 daily cases, yet infections continue to dramatically rise with 6203 new cases of COVID-19 reported on March 26, 19 days later. There is no discernible cause for this effect; is it age, people’s pre-existing conditions, high pollution, inaccurate testing, little fairies in the air?!!! etc.…

In this situation, we can’t tell what’s going to happen based on what’s come before. Outcomes are emergent, not predictable. By the way, some of you who read the above example already have “the answer” to what happened in Italy. Your brain doesn’t need to think about it much more. If this is you, it is a real-time example of how fast the brain turns something complex into something obvious. In fact, this automatic simplification of situations often leaves us with a sense of frustration about the inability of others to see it with the “clarity’ we do.

To get any sense of what’s happening when in a complex situation we need to create, as Dave Snowden calls it, safe-to-fail experiments—taking limited actions to produce outcomes we can learn from. In safe-to-fail experiments, negative outcomes are suppressed while positive outcomes are enhanced and built upon. The airline industry has truly mastered evolution in Complex arenas, as evidenced by their transformation in safety starting in the 70s. Black Box Thinking by Matthew Syed is an incredible articulation of this, contrasted with the medical field’s relatively untransformed safety record.

In complexity, we must lean on the expertise and views of other people while simultaneously increasing the diversity of people we speak with. The objective is to allow the collective intelligence to reveal answers we would never come up with on our own. This phenomenon is called the Wisdom of the Crowd or, in more rigorous terms, Distributed Cognition. As we increase the diversity of the network, we encounter new thinking, new answers, and new actions to attempt.

In a safe-to-fail mindset, we are testing prospective answers and taking small steps—probe, test, see what happens, learn and iterate. Keep doing this until a stable pattern reveals itself. This is the domain of emergent practice. An algorithm emerges that gives us some predictability. These emergent practices have a short half-life and only work for a limited time due to the system being in continual flux. Leading different personalities, parenting children, creating effective corporate culture, and navigating conflict are examples in the complex domain. Learning to ride a bike is squarely in the complex domain. At the time, these challenges occur as rocket science.

In a Chaotic situation, there is no connection between cause and effect; we can’t make out any pattern. The first action is to stabilize the system and, in crass language, “stop the bleeding”. Only then we can start testing and experimenting with ideas and actions in hopes of finding and building on some evidence of cause and effect. So counterintuitively, in a chaotic system, the first response is to act and not to be paralyzed by analysis. What emerges may begin to reveal another clue as to what cause is behind what effect.

Acting in chaos is easier said than done! Most of us are so addicted to analysis and the need for certainty that we experience serious hesitation and doubt which prevents the necessary first step of acting. We must be able to tolerate the state of “not knowing”, such that we can take an action, any action, and give ourselves a fighting chance to learn something. Persistently taking action after action will eventually yield enough data to reveal a pattern that will reduce the Chaotic to the Complex. Unfortunately, most of us will try this for a while, but we quit when we don’t get the answers we seek or see any “light at the end of the tunnel”. Resilience and a high tolerance for failure is of central value.

This is the domain of novel practice— almost all scientific breakthroughs have occurred as a function of a scientist having the wherewithal to iterate new actions, test and probe, in the face of no obvious cause and effect while experiencing continuous failure. Relentless action and testing eventually leads to a breakthrough, or we run out of time. The relationship between hand-washing and disease reduction and the formulation of Constructal Law are two examples of finding a pattern in what is initially Chaotic. These flashes of insight look like an accident, or luck, but were only made possible by the commitment to iterative testing that preceded the flash.

Disorder is Natural

At the center of the Cynefin model is Disorder. Disorder is the constant state within which the other four systems exist. In fact, this is not just an interesting concept; it is The 2nd Law of Thermodynamics, which states that the entropy (randomness and disorder) of any isolated system always increases.

What’s the relationship to business? You and I live in a business environment where all our systems, processes, and structures are constantly degrading into a state of disorder. This isn’t an opinion, it’s physics. Look for yourself. The moment after you finish drafting a new policy and they say they understand it, one by one they predictably begin to forget and just do their own thing. In the weeks and months to follow, they return to old behaviour and it appears that you never said anything at all. But, you, me and almost all leaders live opposite to the disorder. We live as if order is king. We get surprised and even upset when our nicely arranged plans and expectations fail to materialize, behaving as if disorder is unnatural and out of place. What we said once, or twice, or a number of times should stick – damn it!

Why Do You Simplify the Complex?

The first opportunity here is to accept and even surrender to the fact that you – like the rest of us – are firmly gripped by the human condition of turning the complex into something simple and obvious.

Consider the notion that as a leader you default to simplifying complex issues without fully grasping the nature of what you are simplifying. One source of this persistence is how our brains evolved. Your brain is only 2% of body weight but uses 20% of all your calories. It is a glutton. Given its energy consumption, the brain has evolved to create shortcuts so you don’t have to think too much. This habit of simplifying the complex evolved over millennia to conserve those precious calories gained from the mammoth you and your cave-pals just took a week to hunt, kill, skin, cook, and eat.

Your brain has evolved to navigate the actual complexities of life by creating shortcuts. In the boardroom, shortcuts sound like, “I get the point, can we move on?!” In other words, your brain hates burning another molecule of glucose to think about someone’s point unless it absolutely must. It is constantly saying to you, “This is like that; not worth examining.” It doesn’t take much to begin to see the likely consequences of this.

Falling from the Cliff

The negative consequences of constantly simplifying complex issues accumulates. Eventually, we reach critical overload and, as Dave Snowden says, “fall from the cliff”. In other words, we suddenly drop from the Obvious domain into the Chaotic. In real life, this shows up as an unexpected catastrophic event. It plunges the person, the organization, the country, and even the world into chaos. See the following three examples:

#1 At the Personal Level…

One need only look as far as the > 50% divorce rate in most of the Western World. What might surprise you is this finding from the largest ongoing British household survey in history, Understanding Society, “…it’s clear that a majority of divorces—and the vast majority of splits among unmarried couples—come out of the blue.” Said plainly, most people who divorce never saw it coming. This state of simplified ignorance and “bliss” is further made obvious by the testimonies of over 80% of divorcees that they thought the other person was happy and things were fine. This reveals our human addiction of taking the inherent complexity of another person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and simplifying them so we can get on with our own agenda.

You are neurologically wired to encounter life this way. You compare what you see to memories from the past, find a close enough match, take a shortcut, and move on without evaluating the efficacy of the decision. In fact, you will even go so far as to justify and rationalize negative outcomes. This constant and rapid categorizing, comparing the present to the past, is made inescapably obvious from studying how people see things.

“If visual sensations were primarily received rather than constructed by the brain, you’d expect that most of the fibers going to the brain’s primary visual cortex would come from the retina. Instead, scientists have found that only 20% do; 80% come downward from regions of the brain governing function like memory.” – Richard Gregory, Brit. Med. Journal 1998 317:1693 – 5.

Richard Gregory, a prominent British neuropsychologist, estimates that visual perception is more than 90% memory and less than 10% sensory nerve signals.

In layman’s terms, you and I do not see life insomuch as we are constantly remembering it. Your brain is always shortcutting the present and converting it to some extension of the past. “The more things change, the more they stay the same”.

#2 At the Organizational Level…

Prominent companies have failed because of this desire to reduce complexity. Many failed because they ignored the data that revealed the anything-but-simple and seemingly secure nature of their position in the market. The current posterchild for this phenomenon would be Blockbuster, who turned down the opportunity to buy upstart Netflix. As recounted in GQ Magazine, when Marc Randolf and Reed Hastings pitched then-CEO John Antioco on buying Netflix for $50M, Marc recalls Antioco’s reaction:

“… a turning up at the corner of his mouth. It was tiny, involuntary, and vanished almost immediately. But as soon as I saw it, I knew what was happening: John Antioco was struggling not to laugh.” In 2018 Netflix grossed over $16B and Blockbuster has been wiped off the face of the planet.

#3 At a National Level…

One could argue that most of history was shaped by the human condition of reducing complexity to something obvious. One great example is the Maginot Line built by the French to protect from future German invasions after WWI. French leaders spent $1B French francs to build armaments based on the shortcut thinking from the past. Ultimately, Nazi forces cut through defenses designed against 20-year old technology, surrounding and defeating allied forces. This has become a flagship example of the devastating consequences when human beings reduce the complex to the obvious.

The current state of the Climate Crisis reveals the modern results of perpetually marching out “simple solutions” to the complex and mounting catastrophe of non-renewable energy consumption.

So How do you use this?

Different situations require different ways of navigating. And you’re wired to underestimate disorder, chaos, and complexity.

When everything you know, all your best stuff, isn’t working anymore you’ve entered a state of disorder. Nothing is going to be immediately ordered and obvious. And the longer you try to bring Obvious, or even Complicated strategies to the situation, the longer you’ll be in Disorder and the deeper you’ll go over time. This mismatch often results in debilitating thoughts like, “I should know better, how come I don’t.” or “I should be further along by now, what’s wrong with me, what’s wrong with them?!”

It’s ok to be confused, stressed, guilty, scared or angry. It’s ok, really. In fact, it’s the most natural reaction you could have. In Chaos, when everything is exploding, when the walls are tumbling down, the first thing to do is to just act. Trust your instincts in these moments of chaos. They will serve you better than your lifetime of knowledge and your desire for analysis. Act, sense, and only then respond in a way that has a chance of moving you, your team, and your company into another domain.

Your job right now is to move from Chaos to Complexity and then from Complexity to Complicated. This will require acting in small ways, learning, and evolving. It will require hearing from a diverse group of people from within and beyond your industry, people that until now did not occur for you as assets. Lastly, it will require avoiding the continuous temptation to analyze, optimize, and simplify.

There aren’t any good, reliable, long lasting answers right now. You’ll only figure out chaos and complexity one step at a time. The good news is, you’ve done this before. The first time you became a leader, you had no idea what you were doing. Right now, none of us do. But you, we, leaders everywhere get to learn how to use failure, how to experiment, even to play. Maybe “normal” wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. We could use this time to reinvent why and how we work and become something more purposeful and nimbler than we ever were.